Chýnov Cave - history

Quarries

The name of Pacova Mountain is not derived from the town of Pacov as one might believe, but originated as people mangled the original name of the Pecová Mountain, given for the numerous small ovens for baking lime. Limestone was also quarried near Kladrubská Mountain and in other minor mines in the surroundings. Although the quarry at Pacova Mountain was not mentioned explicitly until 1747, historical sources allow us to assume that the lime industry existed in the region as early as the 15th century. The fundamentals of the present, now abandoned quarry, were laid in 1857, when the large calcite bed was opened along the entire slope of the hill. The exploitation increased as the demand for quality product from the Chýnov region soared. 1878 saw the construction of the third large furnace for baking lime and on 14 August 1879 the first road steam truck to be operated in Bohemia began transporting lime to Tábor. As the company had a good management and organization, it flourished and in the years preceding World War I it employed 260 workers and produced up to 17,000 tons of lime per year. The company constructed narrow gauge railway transport connecting its plants and operations, the production of gravel and bricks. The tradition of the lime industry in the region did not diminish until 1964 when the exploitation of limestone was terminated and from that time onwards only stone has been worked there. The last of the lime works at Pacova Mountain was destroyed in 1972. The works in the quarry did not cease until 1998, when the last, 370th blast was carried out. The abandoned quarry and its surroundings are nowprotected as a natural reserve.

Cave

Although several large mines had been opened up by the mid-19th century at Pacova Mountain, the entrance of Chýnov Cave was discovered in a small farm mine on the southern slope of the hill. Vojtěch Rytíř, a quarry worker was working in the quarry in summer 1863. He is said to have dropped a hammer, which sank into a fissure in the rock. In order to find the tool, he had to get into the fissure himself. Surprisingly, the narrow crack changed into a wide corridor and continued further underground. We do not know whether he actually found the lost hammer; however, we know that he discovered the entrance to Bohemia's largest cave of that time.

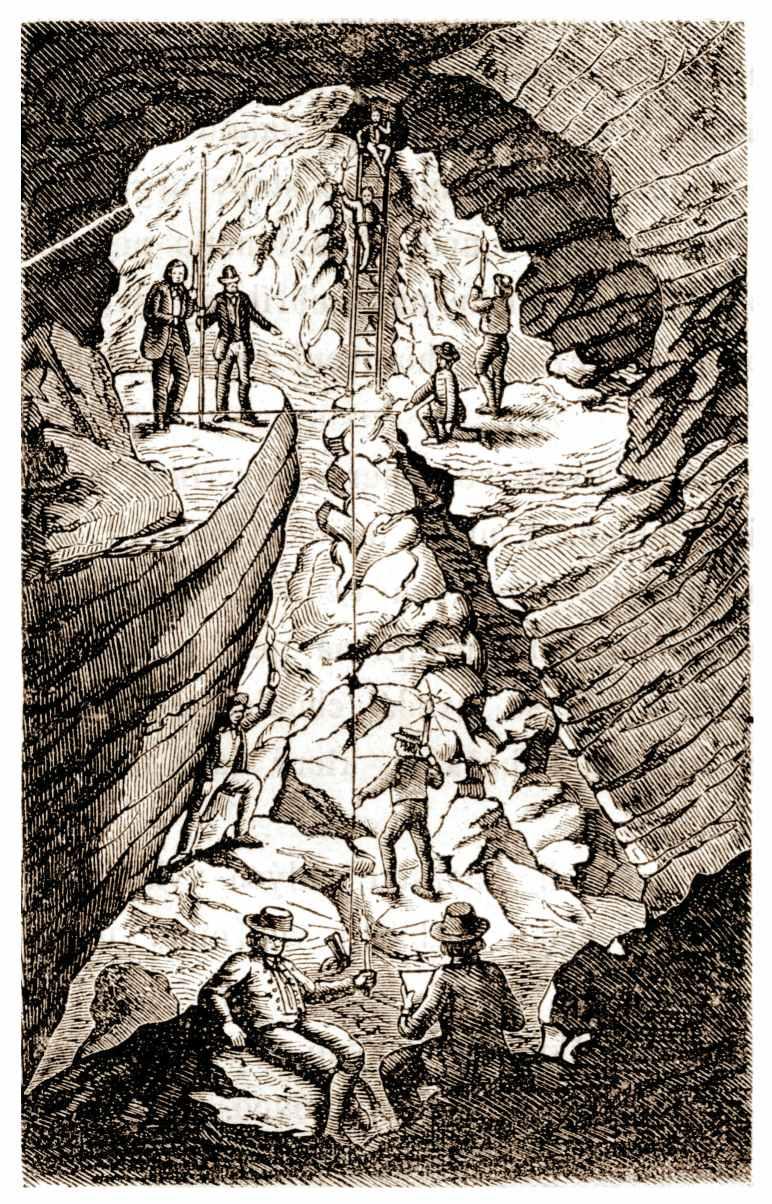

“The first to dare go in were: Jan Strnad, lime supervisor, and Josef Janů and Jan Švehla, quarry workers. Carrying torches, they went through all the corridors of the cave and came out after long wandering. …Striding boldly we were descending down the Giant or Devil’s Stairs, stepping on huge boulders fallen from the ceiling when suddenly we saw the glitter of water in a distance, reflecting the light of our torches and announcing that we had reached the bottom of the cave." - This is the account of the exploration of the cave given by the then custodians of the CzechKingdom’s Museum in Prague, Antonín Frič and Jan Krejčí, who surveyed the cave together with Ing. Wette several days after the discovery and drew the first map of the underground areas.

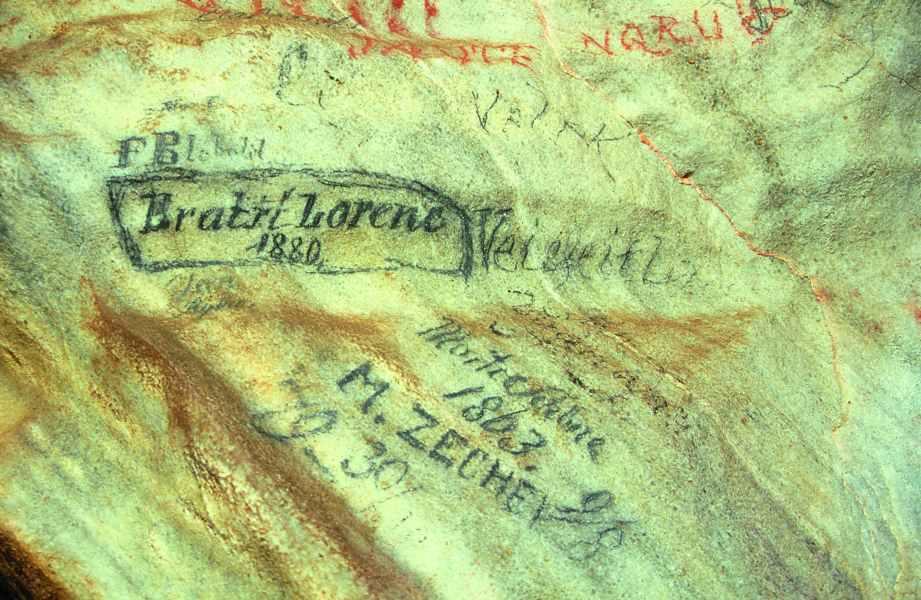

In 1865, Josef Rothbauer, a peasant from Dolní Uhřice, began to work in the cave. He excavated the sediment in the low corridors, placed ladders along the steep slopes and adjusted the entrance so that the cave could welcome its first visitors in 1868. However, the work did not cease then. On the contrary, Josef Rothbauer, and especially his grandson, Václav Rothbauer, are highly credited for the sensitive and romantic stone stairs, bridges, their participation in the exploration, maintenance of the area and assistance during the electrification of the route round the cave in 1952.

Vladimír Homola, a student, began his career in the cave in the late 1930s drawing on the initial exploration conducted by Krejčí and Frič. He discovered several important parts of the system and studied the geology, hydrology and morphology of the Chýnov Karst. He also made the first detailed maps of the cave. In 1962 František Skřivánek proved the connection of the subterranean stream with the karst spring of Rutice. In the following years speleologists managed to discover a number of further underground areas, including some that were permanently flooded.

Meanwhile the cave attracted growing numbers of visitors reaching some 40,000 a year at the end of the 20th century. This, as well as copious other factors led to the necessity of comprehensive reconstruction of the tour route. In 2006–2007 the complete electric installation was replaced, further areas were made accessible and a new exit gallery was dug. However, the cave has not lost its historical nature and is still a romantic stroll through history.

OVERVIEW OF DISCOVERIES MADE IN CHÝNOV CAVE

- 1863 – Rytíř, Strnad, Švehla, Janů, Discovery of the cave and corridors: Schwarzenberg’s, Malovecká, Corridor of Slavník’s Dynasty

- 1939-1940 – Homola, Corridors Muddy, Parallel, Connecting, Steep, Water Chambers

- 1942 - Homola, Rothbauer, Sticky Corridor

- 1944 - Homola, Schüller, Homola’s Lake

- 1962 – Skřivánek, Tracking test – karst spring of the subterranean stream, Labyrinth

- 1962 - Tymmel, Pášma, Veselý, Twist Corridor

- 1982 - 2005 – Czech Speleological Society - ZO Speleoaquanaut, “Bottom level” – permanently flooded areas

- 1993 - 2007 – Czech Speleological Society - ZO Chýnov Cave, Cascades, Entrance Corridor